Radovan Matijek ((Photographer: Peter Thielen)

“In the process of developing a sculptural construction, it inevitably arises my subconscious autobiographical dualism between dynamic dance movement and that one halted in one sculptural statics” said Radovan Matijek, talking about his sculpture Clamor Lugubris in a interview we had in December 2020.

An unbelievable life energy, power and courage radiate from the whole work of Radovan Matijek. During his studies at Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb in Croatia, he danced in an ensemble for contemporary dance, presented performances and exhibited in solo and group art exhibitions. Later he has expanded his artistic expression to acting, film production, scenography and choreography and he has specialized butoh dance. He was born in Split (Croatia), where he still has one of his studios and where he gets new ideas for his work. The other two studios he has in Germany, where he lives after spending some time working and studying among Berlin, London, Amsterdam and Paris.

His work indicates a high creative potential, which he by the power of his talent and broad knowledge directs towards the creation of impressive work. The uniqueness, aesthetics and expression of his work attract viewers attention, leading them to think and reflect.

It was a great pleasure and enrichment to talk to the artist Radovan Matijek whose new projects are awaited with great curiosity.

Jasna Lovrincevic: “In the autumn 2020 you exhibited a sculpture called Clamor Lugubris at Kreislauf 2 exhibition in Kranenburg and an installation at Katharinenhof Museum. At the same time, the play Kaltes Herz (The Colden Heart) for which you have created puppets and objects was shown at Hof Theater on the other side of Germany and you worked with Sabine Seume as a stage assistant for her dance performance Infinity at Atelier for Performing Art in Düsseldorf.

Through these three different simultaneous artistic events, it has been presented your artistic personality focused on different forms of art expression.

How do you feel about a situation like this where you are presented by different art forms

at three different distant places at the same time? ”

Radovan Matijek – Clamor Lugubris

Radovan Matijek: “First of all, I am a artist of fine art, sculptor and then a performer. But I almost always intertwine several media, I am quite present in the theater, I do special objects for various theater productions collaborating with various directors and choreographers. I act and dance and I make objects and create complete theatrical scenery. I make choreography and I exhibit my work.

This year 2020, there was a lot of turbulence due to covid 19, many projects have been canceled or postponed. Here, however, I have successfully realized three projects between the two ‘lockdowns’.”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “Your sculpture called Clamor Lugubris I associate with two figures in a butoh dance pose, perhaps knowing that you are known as a longtime dancer of that dance. Could you please tell more about the sculpture and your installation with glasses exhibited at Kranenburg until mid-November? ”

Radovan Matijek: “Kranenburg is a small, picturesque town. It is the place with the Pilgrimage Church and Way of St. James leads through it. Twenty German and Dutch artists exhibited their works in the outer circular belt of the town, between the walls and the water, and in the Museum.

Radovan Matijek – Clamor Lugubris

The sculpture Clamor Lugubris (Lamentation) is displayed at the beginning of that circular belt.

In this object, I have combined one insectoid and one floristic form. The sculpture stands on four legs which look like the legs of an insect. Out of the body twist two elegant necks ending in two stylized flowers, which look like wide-open mouths from which emerge vibrating tongues screaming toward the heaven. It’s actually a 4.5 meter high mutant.

You have nicely noticed that in the elaboration of the sculptural construction itself, it inevitably arises a subconscious autobiographical dualism between dynamic dance movement and that one halted in one sculptural statics.

But the dynamics is timed, the feeling is that the creature will move in a new direction at any moment and start to beat us on the heads. We should not forget Chernobyl, Fukushima… not to close our eyes to the flames of fire which swallow the Amazon, to the plastic which floods the oceans, to the CO2 which suffocates the already congested atmosphere, and our egocentric mind…

The sculpture is bright yellow and it has high´gloss. It is a bit robotic, futuristic and yellow colour is a sign of optimism at all this negative perception of the sinking world.

I hope deeply and sincerely that my multiplied sculptures of this type will not adorn the future gardens of a lost paradise.

At the Museum, I exhibited one installation of broken glasses called Fragil.

Radovan Matijek – Fragil

On one larger table, I set a hundred broken wine glasses without chalices or pedestals. Instead of missing parts, they carry thin branches of finely processed wood. The fragile, almost delicate constructions of inorganic glass and living wood have a metaphorical meaning. Broken glasses symbolize the fragility of human civilization which is always destroyed by wars or natural disasters. Each war leaves behind dead and wounded, ruins and ruined identity. It is questionable how something new can emerge from such seemingly hopeless remnants.

But each shard carries within it a small remnant of identity remanding of what it was before the disaster. The branches growing out of broken cups symbolize emerging life. This installation speaks about fragility of human life and about conditions under which a traumatic identity can be redeveloped for the good without concealing the ruptures and deformations left behind by the trauma. There is reason for quiet hope, but not superficial optimism.”

Jasna Lovrincevic/strong>: “In 2018 you participated in an extraordinary and significant German-Dutch project Brokopondo, travelleing to the state of Suriname where you exhibited an interesting wooden object called Lucifer (Mach). In fact it is the Dutch word for match as you have explained in our introductory conversaton.

Could you tell more about this project. Did you use the wood taken from an artificial lake, created by constructing a hydroelectric plant, actually wood from a submerged forest?”

Radovan Matijek – Brokopondo Project

Radovan Matijek: “Suriname is a small country in Latin America, a former Dutch colony whose area is 80% covered by the untouched jungle under the protection of UNESCO. Dutch is also the official language in that territory.

At the invitation of the Seewerk Gallery and Museum in Moers, I joined to ten selected artists for the Brokopondo project. Back in 2013, I exhibited at Seewerk Gallery, among other pieces, an installation called Streichhölzer, translated as Matches. Some twenty twisted “trees” whose ends are burnt blackened heads, actually make one burned forest. Such activist accents were followed by this invitation for Suriname.

There I made a sculpture of Lucifer, in Dutch it means a Match. It is made of hard wood ‘walaba’ which has been preserved in the fresh water of the Brokopondo Reservoir for thirty years.

The sculpture is 7 meters high and it is displayed at the New Amsterdam Open Air Museum at Paramarib, the capital of Suriname. When I returned to Moers, I made a very similar object which has been permanently set up in Seewerk Park.

My matches are accents against the burning of rainforests and the uncontrolled exploitation of wood in the Amazon and other rainforests across our planet. ”

Jasna Lovrincevic: You are graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, in the class of Prof. Stipe Sikirica. In spite of the fact that you were educated in some way by traditional classical approach you already as a student presented various installations. What challenges was the combination of modern and traditional presented for you at that time and what about nowdays? ”

Radovan Matijek: “Although I graduated in the class of sculptor Stipe Sikirica, I was already involved in installations art work at the time, which was a continuation of world and Croatian avant-garde heritage. Later, I have participated in my own installations as a performer.”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “Your biography is very rich, in addition to sculpture, dance and theater, it also includes work on film. In 1990 you produced the film Cej for which you, together with your collaborators wrote the script, did choreography and you were director. How did you start to work on that film and where has it been shown?

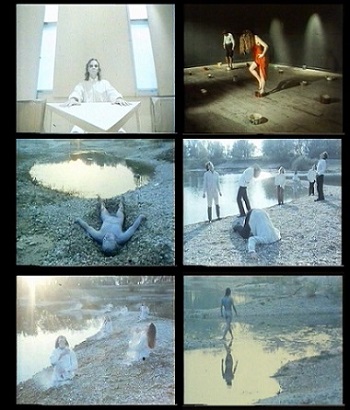

Scenes from the film Cej (Digitized by Miodrag Trajkovic)

Radovan Matijek: “The film came as a spontaneous reaction. We were looking for a venue for our new play and we didn’t find any theater where we could stage it and we decided to make a film. That was before the war (in Croatia), I act, dance and direct together with a colleague Ljiljana Mikulcic. The material was recorded in 1989. The title Cej has no meaning, it is just a sound or sigh.

It was a premonition of our war when people even didn’t think about it. We made a film about the horrors of war in an allegorical, metaphorical expressions.

It is a short film, it is a sound film, and there is no text. The film has been shown at many festivals, it lasts for 34 minutes, and it has been shown in France, The Netherlands and Germany on the television channel Arte. ”

Scenes from the film Cej (Digitized by Miodrag Trajkovic)

Jasna Lovrincevic: “Have you continued with film production?

Radovan Matijek: “Between then and now I have produced several short films mostly related to my art or dance performances.”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “You create and make puppets and different objects for various plays at several theaters in Krefeld, Monchengladbach, Essen and Hof as well as for the theater Freilichtbühne Alfter and Westfälisches Landestheater. How do you approach a design of all that objects or puppets? Are you independent at that work? ”

Radovan Matijek – Puppets (Photographer: H. Dietz, Hof Theatre)

Radovan Matijek: “I work in the theater in terms of making special objects and puppets. These puppets are big, two to three meters high, they are mobile, actually they look very lively, they are always animated by dancers or actors. Now, in Hof in Bayern on the Czech border, it is performing the play with title Cold Heart (Kaltes Herz). For this project I have made ten, long fingers. Each finger is carried and moved by one dancer. At the end of the show, a naked puppet which looks like a child stands on the stage supervising the audience by its big blue eyes and staring at it – ‘ the life goes on’.

Ideas arise in conversation with the director according to his needs of visualizing the play. In the realization itself, I have unlimited freedom. ”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “One unavoidable topic related to your artistic expression is dance, especially the butoh. You have danced as a student in Zagreb and later in London and Germany. In Zagreb you danced in the ensemble of Milana Broš, about whom the author Maja Durinovic has written that she (Broš) was “known for destroying elitist and aesthetic notions of art.” Did Milana Broš attract you by her ideas in dance or perhaps have you come under her influence in some way, in terms of dance? ”

Radovan Matijek – Puppets (Photographer: H. Dietz, Hof Theatre)

Radovan Matijek: “At the same time, while I studying at the Academy of Fine Arts, I danced in the ensemble of Milana Broš. She has received a large number of awards for contemporary dance both as a dancer and as a choreographer, abroad and then in Croatia.

Milana Broš at the time, in the mid-80s, was the only one to offer the dancer an avant-garde line within contemporary dance that I immediately recognized as a young performer, desirous for new experiences. I completely agree with Maja’s opinion, by the way, my colleague in the ensemble at the time.”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “You have made numerous performances with the butoh and you have written choreography for it. When did you start to dance the butoh and why do you like that dance?”

Radovan Matijek: “Butoh is an avant-garde, expressive dance, which originated in Japan in the early 1950s. It builds on the expressionist experiences of German dance in the 1920s of Mary Wigma and it brings an unavoidable aesthetic of the Far East with an enormous possibilitiy of improvisation and exploration of one’s own body and movement. Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ono are the fathers of this new stage expression.

And how did I start? I presented one performance in Zagreb with idea to perform one moving sculpture. I intended to play one stone sculpture in motion. I painted myself in white color and I somehow began to move in space. Someone told me it looked like the butoh dance. At the time, I didn’t even know what was the butoh. It was in London, while I was working at the Oktober Gallery, I met a butoh dancer. The dance immediately won me over with its expressiveness and at the same time by its mystery, its spontaneity, the aesthetics of the white body and the so-called ‘black soul’. The butoh is always associated with some dark side of our psyche. I am an artist who likes to try new things, who likes to dig through his own subconscious and complement the mosaic of the world around us. In this dance, the subconscious component, which deepens and opens new horizons, is very important. It allows your own body to move without any control.

Arriving to Krefeld, I have joined Sabine Seume, at that time a well known butoh dancer and choreographer, and I have specialized in butoh at her workshops. Still today, we are close collaborators.”

Jasna Lovrincevic: “I have read butoh dance doesn’t need choreography because of it’s spontaneity?”

Radovan Matijek: “Oh, of course the butoh has a choreography, but also the possibility of improvisation.

There are special techniques to make choreography. Kacogen is one of these techniques or rather a state of mind which progressively moves towards the exploitation of its own body. The process is very subconscious; with half-closed eyes the organism enters a trance state and then the body moves on its own. In this process, one tries to turn off the real mind system and to give the body the ability to expose itself without any control of mind. The movements can be very wild but can also be very slow so there is a wide range of sensation.

Of course, in that process, it is needed a person who observes all this from the outside. Then the choreographic elements are written down. One performan is built on a collection of active images.

Jasna Lovrincevic: ” You always have a lot to say and show. You always express yourself in a new aesthetic way and all your work indicates a high artistic potential and a talent that has no limit.”

Radovan Matijek: “Somehow these are my animations and interest that I have always had: stage and visual art. It’s hard to set boundaries where one art begins and where another. It’s my nature. Everything draws me to something and then it comes out that I have to accomplish it. Why (?), I haven’t thought about it yet. I just go to realize that project which presents a new challenge for me. ”

Radovan Matijek – Pirate Ship- Performance

Jasna Lovrincevic: “It is nice and interesting that you manage to fulfill and present your art ideas, what it is usually not easy and mostly unattainable for many artists.”

Radovan Matijek: “Probably, the collaborators and the audience love and respect me, they appreciate my creations, my way of thinking and acting.”